SESSION II: WHAT IS EDUCATION?

Discussion leaders: Sara Hendren and Chad Wellmon

Stanley Fish, Save the World on Your Own Time (Introduction & Chapter 1)

Jennifer Frey, “The Virtues of Liberal Learning”

Chad Wellmon:

On one level, we can understand education normatively—as a leading out toward some universal truth. But we can also understand education, as Du Bois suggests, as a kind of fitting to the world in which we find ourselves. Fitting, not in the sense of submission or conformity, but as in the work of a craftsman: when you use a jig to guide a saw, you shape something in relation to what already exists. Education, in that sense, is a process of measured fitting—of aligning our practices to a world that precedes us.

In our discussions so far, a modal distinction keeps surfacing between the university as it is and the university as it claims or ought to be. For me, this invites reflection on the relationship between education and the university—how practices of teaching and learning come to inhabit particular institutional forms, sometimes by design, sometimes by historical accident. As I argue in After the University, following MacIntyre and Stout, it’s useful to distinguish practices from institutions. Practices—like higher learning—depend on institutions for their material and social conditions: the classrooms, the chalk, the salaries, the healthcare, the parking lots. To deny that would be naïve. But practices also risk being absorbed or distorted by the very institutions that sustain them.

That tension raises a question at the center of our conversation: Does higher learning necessarily require the university? And, more unsettlingly, does the university necessarily require higher learning? Recent events suggest it might not. My own university, for example, now derives roughly two-thirds of its budget from its healthcare system. Its survival and identity seem tied less to education than to a massive medical enterprise. This is not unique to one school; it signals a broader institutional drift. So we must ask, what happens when the university no longer depends on—or even prioritizes—education?

That leads me to what feels like the more urgent inquiry. Not what is higher education or higher learning, but where is it? Where has education historically been located? Where does it now reside? And where might it take root in the future—the near, the middle, and the long term? Even as an institutional creature, I find myself wondering what new or renewed forms might host genuine higher learning—perhaps within, but also beyond, the conventional university.

Finally, I want to underscore the distinction between higher education and higher learning. Higher education, as I understand it, refers to a particular institutional system that emerged in the second half of the twentieth century—what the Carnegie classifications formalized and the postwar liberal order sustained. It is a social function, an institutional amalgam serving many purposes, of which education is often a secondary or even tertiary one. Higher learning, by contrast, names the enduring practices of inquiry and formation that may or may not be found within that system.

So the question I keep returning to is not “what is education?” but “where is it?”—where it has been, where it still flickers, and where it might yet endure. That, I suspect, is also the question animating Fish’s provocations, even if he never quite names it that way.

“Does higher learning necessarily require the university? And, more unsettlingly, does the university necessarily require higher learning?”

— Chad Wellmon

Sara Hendren

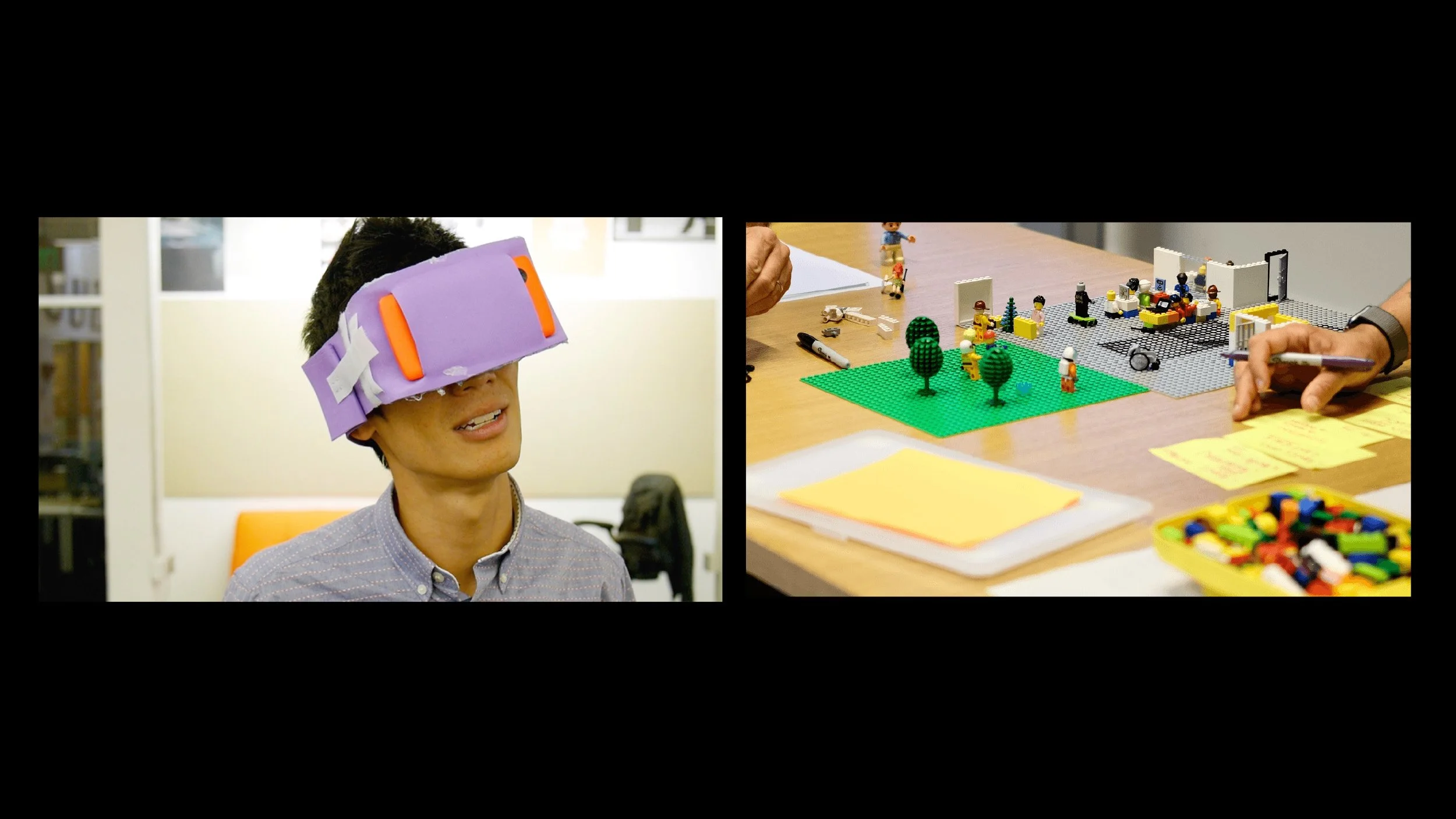

I'm so glad that you teed up where I'm going to take us: to the literal “where.” I’m in art and design and architecture, and for my reflections today, I’ve brought images of actual classrooms, the better to situate us in the material spaces of our work.

I have accidentally found myself a humanist in pre-professional university programs, and I’m always looking for the most exciting possibilities to blend them: places where the pre-professional domains conjoin themselves to the pursuit of democratic practice and wisdom and truth in the ways that we’ve named.

I spend a lot of time and energy in a studio environment, like you can see here. I assume that most of you spend your time not in the studio but elsewhere: in the seminar room. I teach in a mix of both kinds of spaces, and I spend a lot of time and brain cells trying to think about how to take the literal artifacts of the world—these processes of making and doing—and let them be a portal to the philosophical questions, to encounters with ideas about the common good and the public sphere.

I want to speak a little bit about the laboratory, the design studio, and the architecture studio, collapsing them into one for this discussion to complement the seminar room. There is something distinctive happening in these spaces, and I want to add what they might bring to this question of what education is—in a very tangible sense.

Acknowledging MacIntyre’s and others’ misgivings about whether an education in the substantive pursuit of truth is even available, I want to propose today that we look at Danielle Allen’s “readiness” framing to understand education. What should four years in a college classroom make a student ready for? In her Tanner Lectures delivered at Stanford and published in 2016, Allen takes up two kinds of readiness to talk about what an education should deliver. One is “professional readiness”; this idea is self-evident, so I won't spend any time on it. We know what we mean by professional readiness. The other is what she calls “participatory readiness,” made up of three big sets of capacities. Taken together, these capacities in the classroom form a rehearsal space for joining a democracy even in its kernel form.

The first activity of participatory readiness is “disinterested deliberation.” Think of the town hall meeting for this one—the kind of give-and-take discussion of the common good, of desirable worlds and how to navigate a pluralistic society. How do we rid ourselves from our parochialism and try to reason together?

Second, she talks about “fair fighting.” This activity shows up in all strong forms of protest and lobbying. Unlike disinterested deliberation, these actions are explicitly interested, looking to pursue some cause or idea of the good and to be persuasive in doing so.

And third, there's this factor that rather less spoken about—at least when we talk about civics education. And that is what she calls “prophetic reframing,” or we might say “frame shifting” in proper terms of rhetoric. As examples, she points to some of the great rhetoricians in American civic and political life who do this frame-shifting work, in their political speeches and writing, by means of metaphors and symbols and other literary conventions.

Prophetic reframing does its work in a twofold way: It redescribes the present, so we can see it freshly, and it proposes a kind of desirable future. Allen points to experts such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Abraham Lincoln to illustrate strong prophetic reframing. It was not that these people happen to be gifted orators as a bonus to their “real” political work. Not at all. These model figures were able to utilize all three participatory capacities as they were called for, and the rhetorical work of prophetic reframing they each did played an absolutely essential role. In Allen’s schema, students should practice becoming conversant in prophetic reframing as a bedrock skill for operating in a pluralistic society.

I want to suggest here today that the making professions—art, design, architecture—also participate in this frame-shifting work. I want to suggest that designed artifacts and environments can give birth to new ideas in a particular way.

For example, the Church Under the Bridge in Waco, Texas. It meets under a freeway overpass, a kind of makeshift “found” architecture that’s made from infrastructure. This church community was started simply because of a series of encounters and relationships among people living unhoused under the bridge and local Christians. The church now runs formal church services on Sundays and offers social services during the week. What a beautiful form of adaptive reuse, as we’d say in architecture. An enormity of infrastructure that becomes a shelter is surely a work of prophetic reframing: recasting what the built environment is for and what it might make possible.

Or the Dementia village in the Netherlands. This is a locked facility, a nursing home for memory care in the town of Weesp. It was redesigned a couple of decades ago in the simulacrum of a small village. You go through these very barricaded sets of secure doors, but then you see a plaza, streetscape with a grocery store, gym, music room, side-by-side tandem bikes, a pub, and more — the continuity of life in a recognizable “town.” It was designed to preserve the familiarity of designed surroundings and thereby to quell the anxiety that comes with being lost in space, not just in time. Their longitudinal observational data report a dramatic decrease in their reliance on psychotropic drugs for mitigating that anxiety; it’s architecture used as medical treatment.

At De Hogeweyk, there's also a public restaurant, both for people from the town who can go there and have a business lunch and for the residents who live there. Everyone just agrees, tacitly—the wait staff and customers—that there will be enigmatic encounters with patients who live there, but it’s always possible to have a humane interaction. You can think of it “in plan,” we say in architecture—the blueprint aerial view—and you can imagine almost a dotted line around that restaurant. It is semi-public, semi-private, and that makes the difference. Older adults in memory care are not simply closed away from public life; they are having some controlled but preserved interaction. To me this is a kind of prophetic reframing: rethinking what designed sites and interactions make growing old more convivial, and to re-imagine life in conditions of independence.

We might also think of Better Block, a design firm that works with cities and towns to prototype new streetscapes. In a single weekend, they will mock up the way a street or a corner could look in the future so that people can experience in 3D space what that would be like. You'll not be surprised to hear what Better Block has witnessed: that if you're just debating a 2D image or a list of principles for the future of your city, you'll be stuck in committee for the next two or three years, debating in the abstract what the future should be like. Better Block speeds up and vivifies the process; they take all the effort to bring in, say, mature trees and furniture just for a weekend, because they believe in this spirit of reframing: giving three-dimensional life to a new idea.

I think humanists often imagine that a good built environment can only follow from a strong democracy — that design can only live downstream from good ideals. I want to suggest that in fact the causality can also run in the other direction: that design can also shape ideals.

Better Block’s practice looks a lot like the design studio classroom or the engineering lab. In those educational spaces, you’ll see lots of very playful experiments built from scraps and detritus—we call them low-fidelity prototypes—where you're just batting around ideas and trying to figure out: how would this work? There’s nothing more formative and critical for any university student than the seminar; I’ll seek that condition of dialogic exchange for the rest of my career. But I also observe—in myself and in students—a restlessness at a certain point. In a studio environment, we can say to each other: stop talking and show me what your idea could be like. It's one thing to diagnose what's wrong with the world. Have you tried building something?

This was Eboo Patel's big switch, right? Somebody said to him: “Young man, you have a lot of good diagnostics about what's wrong with the world; you should get to work building something better.” It takes both humility and fortitude to take up a new idea.

I think the STEM disciplines in particular occupy a kind of monolithic space in the heads of some humanists. We think STEM is all one big place with all the funding, all quantitative reasoning, all rational planning. But my experience is actually that at its best, some STEM labs require this mixture of humility and fortitude. Prototyping lives best alongside strong, rigorous thinking.

Just one story to end: There's a two-semester class at Olin College of Engineering, where I taught for the better part of a decade called Quantitative Engineering Analysis; it’s a complex course combining math, physics, and engineering. One critical unit is having students each build a boat that travels and holds its stability. Eight weeks before this photograph was taken, the students were given a prompt to just build a boat that floats and travels. And of course almost all of them sink immediately. Utter failure. And then they go to work doing what we expect: the analysis work of multi-variable calculus, a branch of mechanics called statics, and fluid dynamics. And they spend eight weeks doing the math over and over again. And then they finally build their new boats equipped with this knowledge. They get to this moment where they have to see whether the boat actually floats. Show me. Stop talking about it: show me how. It’s a robust fortification exercise. I can’t tell you just how beautiful it is to see what happens in the studio or the lab: the agency of the builder. The agency of the builder that, when conjoined to a strong liberal education, makes possible the conditions of prophetic reframing. Building a desirable world together.

“Everybody’s a critic—it’s really easy to diagnose what’s wrong with the world. Have you tried building something?” — Sara Hendren

David Decosimo: It seemed to me that there was a bent to those three skills from Allen where at least two really central things I think go missing. One is the ideal of civic friendship in a pluralistic democracy. And the other is the idea of something like reflective tending or something alongside prophetic.

I’m struck by the tension between the possibility where education is about, and this is I think particularly evident in a model like Sarah’s oriented toward giving students the skills to generate a product. In Aristotelian language, it’s a techne, there’s a set way to be able to do the thing. Once you figure out what the thing is, and that doesn't mean there isn't a dialectical character and a dynamic character, but it's aimed at generating something external, whether that's a bridge or a boat or whatever. Whereas what Jen, I know part of what you want higher education to be is oriented toward not just intellectual virtue, which is not something externalized as a product, but a formation of mind that disposes one well to the truth. But more than that, you want education to be, or higher education to be a formation of character. And it is true that in the past the university has been that. But it’s also true that in the past, at least in the medieval context, you are praying together multiple times a day, you’re living together and there’s a clear vision of the human good. And it’s not just the classroom, but the whole of life ordered around that.

Jennifer Frey: I’m interested in what people think of Stanley Fish. I seem him as a warmed over Weber—this idea of the scholar as just the expert. When you try to overstep you are misunderstanding what a scholar is, but you're also just bound to fail? And Fish has an answer to what a higher education is, and it is the most common answer that you will get today, and it is to create experts. But go back to the Harvard report. A society of mere experts will never be well ordered and it couldn't be right. It could not be because the expertise itself has to be organized towards something and Fish just seems to say, “Well, that’s somebody else’s problem. Maybe if you want to know about the highest good, go to church or form a book club or whatever. But that is just not our business.”

“A society of mere experts will never be well ordered.”

— Jennifer Frey

Now, historically, that's totally out of joint with how the university understood itself. I've learned so much from reading Chad’s work on kind of the development, especially in the 19th century, of the modern research university. So there's a long and complicated story about how we produce someone who's so confident that the initial kind of vision of liberal education is really something to just be poked upon at, right? You’re just some quixotic joke. Our job is to create experts. That’s what we do. We don’t have any other job and no matter what an undergraduate comes to study, they’re just going to get a lot of skills that are useful for life. There’s no moral formation. You’re going to get the skills, and that’s all we do. And there’s just nothing else that we should be doing or that anybody should ask us to do. And having any vision of something higher is just dramatically misplaced.

John Inazu: I am beginning to think that half the reason for this gathering is just to help me better name my own longings. And this discussion has been helpful in that way. Sarah, your ending anecdote reminded me that I also was an engineering major. Our big capstone project was addressing the hog waste management problem in North Carolina. We were literally out there dropping hog poop from different heights and measuring viscosity and angles and that sort of thing. This is when I decided to go to law school.

But there was something in the culmination of the doing and the bringing together of the knowledge, but importantly with other people. I mean, we ultimately just totally failed and convinced nobody. But even in the failing, we did this thing together and it still felt like capstone in that way.

In law schools, as Fish notes, we have all these internal battles about what the clinics are doing and how the externships are going and who gets credit and when. But what we don't have is much of a sense that we are collectively ever doing some activity called the formation of lawyers. We each do our own thing. And then at the end we sit together at graduation and watch them come across the stage and hope they’re on the way to being lawyers. And that feels very shallow to me given the alternative possibility of doing some collective project together where we're actually saying it matters that you do this in the first year and that in the second year and so forth. And this is what success might look like and this is what failure might look like. But there's not even the beginning of a vision of that. We're just all doing our own thing.

“We’re just all doing our own thing. And that feels very shallow to me given the alternative possibility of doing some collective project together.”

— John Inazu

Sara Hendren: Your engineering example pushes against the idea that the product is always the end. I mean, you had this project failed, but the conviviality that's built and the humility of realizing “the best laid plans. . . .” To me that is a rich area of formation.

I commend you for pairing Jennifer Frey’s work with Stanley Fish’s work. They’re paired because they represent two ends of the spectrum. But missing to me from both is a kind of commitment to pluralism in higher education. A normative sensibility that kids are so different. And this idea that there would be one model that would serve every kind of mind, especially with the explosion of all kinds of techniques and medicines and practices that have expanded our ability to take kids who 20 or 30 years ago would not have been able to matriculate in institutions of higher learning because of anxiety or depression and neurodivergence. And now they can. And it’s a beautiful, wonderful thing.

I think we’re just the very beginning of beginning to acknowledge what that means for the project of the university to have all of these very different people here. So I was kind of hoping for more of a pluralistic vision to make sure that kids end up in the right institution for them that’s not based on income or social cultural capital or background, but actually based on where they might thrive. So I want to call for more of a flourishing of lots of different models than what we have represented in the room with Frey and Fish.

I think Fish provokes us because part of what concerns me about if we have an explicit commitment to a moral training of students, then we have to engage as a university in inquiries in hiring faculty of what that moral training looks like for them in ways that make me deeply uncomfortable because that it's not based on purely kind of an expertise and a commitment to teaching and a commitment to strong and rigorous pedagogy, but it's a commitment to a specific vision that of what the outcome looks like. And I worry that it's kind of a pivot back to homogeneity. I despise the homogeneous university. I think the university thrives when there’s lots of different kinds of people in it. I have limits of what I think could thrive there with Fish. But I think Fish is on to some things.

I think his big misstep is that he mistakes the work of faculty in the research university for the work of all faculty in all universities. Rather than finding a single normative vision, I'd like to have lots of pluralistic iterations, but ones that are each very rigorous within their model, so that are constantly questioning what their model is. I want there to be room for faith-based institutions. I want there to be room for historically black institutions. And I want there to be room for the elite schools and the community colleges, again, all of which are being tested by the metrics of what they’re producing and subjected to much more rigorous stress testing.

Johann Neem: I found Fish to be more pluralistic than I did when I first read him years ago. When I teach “General Education for a Free Society” to my students, I want to inspire them and to make them think their classes in general education are worthwhile. But I know it’s radically unstable. I think what Fish is doing here is confronting the epistemological limits of any institution built on the arts and sciences. And this is where I think he's a pluralist. He’s not saying we do not embody moral traditions and civic traditions. We do. He’s saying “What I am offering to people with those moral and civic and ethical traditions is a knowledge of the arts and sciences. And they are going to embrace and engage in that in pluralistic ways because they are ethical civic beings who are now learning the arts and sciences.”

The challenge is—because I’m drawn Jen to your model of true, good and beautiful—the arts and sciences are not about the true, good, and beautiful. They’re about the development of knowledge through disciplinary practices that reflect a certain enlightenment understanding of the progressive nature of truth. And that truth is never finite; it is never done. It can never be handed down. That’s why “General Education in a Free Society” falls apart at the end of the day—it actually can’t sustain itself. I think Fish is trying to be honest about that limit. He’s not saying the people themselves are limited to this, but that the epistemology of arts and sciences can only do so much. If you want to do more, you need a different kind of institution that is not the arts and sciences. And if we want to do that work, then we have to imagine a university that is not grounded on the arts and sciences.

Roosevelt Montás: Johann, can you explain a little bit further what you mean by the arts and sciences? I’m having trouble reconciling that label with what you are ascribing to it.

Johann Neem: I basically mean the modern disciplines that emerged in the wake of the Enlightenment that replaced the kind of classically defined university where knowledge in the classical university culminating in an ethics course often taught by the minister or president was truth handed down. Now, it doesn’t require less critical thinking to learn truth handed down. Because to understand that material deeply, to really understand geometry, or the nature of God’s universe, requires deep critical thinking. But it’s a critical thinking around understanding. The modern arts and sciences displaced that with the idea that we have scientists who are seeking new knowledge because knowledge is no longer static and therefore, it displaced the authority of culture because it meant there is no single thing to hand down. “General Education in a Free Society” is trying to say we need to do both. I want it to be there, but every time I read it, it can’t. And I think Fish is trying to tell us, “Yes, I know it can’t, and we just have to be honest about that. It can’t and let people bring their complex selves to us and add this modern understanding of knowledge to it.” So I guess that’s what I mean: the modern arts and sciences that created the modern disciplines that form the basis of the university bureaucratically as well as epistemologically.

Chad Wellmon: I want to add two quick historical conceptual notes. I think you could argue that the real innovation of the 19th century Prussian university—the research university—was ultimately 60 years after Kant had made the argument, to upend the relationship of the faculties. Arts and sciences, which for 500 years had just been a super short gateway to one of the professional faculties in which theology had always been superordinate, was suddenly the one with all the power because they examined the Prussian bureaucrats. And then you don’t have the PhD until the very late in the last two decades of 19th century in any American university. And then second, that interesting moment, my favorite moment in “General Education in a Free Society,” where the committee does all this, it's very inspiring. And then they say: “But we do have to be honest. Now that the US has no shared religion, we’re not quite sure what is going to be the base structure.” And they're very forthright about that. They offer up this vision of citizenship, but right after they had just said “this might or might not work.” And then of course it doesn’t.

Frank Lovett: I want to go back Fish’s critique about general education and character formation. I’m sympathetic to that critique, but I want to sort of modulate it in one way, which is that I do think character formation is part of what we should be doing. But it can’t be character formation in general. It has to be something more specific than that because of the reality that only 40% of the population goes to college. So what about the other 60%? They just don’t get formed characters? Is that just too bad for them, or do we think that everybody should go to college? I think we have to think about what kind of formation we’re talking about. It can't just be general character formation, unless we’re just going to write off the 60% who don’t go to college.

It has to be character formation of some much more specific kind. And my temptation is to say that at some point the university became the place where elites get trained and therefore what we’re really talking about is character formation of elites. But it didn’t have to be that way. That task might not have been taken on by intellectuals. And in that counterfactual world, Fish would actually be right. There would be, if the university were just about knowledge transmission, it weren’t about training elites, then it might be that we don’t have a responsibility for character formation. It’s just that we live in a world where those tasks were merged for better or for worse. And therefore, in addition to transmitting knowledge, we're also responsible for training elites. And that comes with a certain responsibility to perform the character of those elites.

“Liberal education is not about the transmission of knowledge, but about the formation of a certain kind of human being.”

— Roosevelt Montás

Roosevelt Montás: I find it useful to make a distinction, which the Harvard Report makes, between liberal education and specialized education. And you can call it serve education or vocational or pragmatic, but liberal education versus specialized, the intellectual framing that Fish gives the project of the university is a specialized one, and it's one that thinks of the arts and sciences as disciplines that produce knowledge and expertise. And it is that intellectual framing that squeezes out liberal education, which is not about the transmission of knowledge, although it uses a transmission of knowledge for cultivation. It is about the product of a liberal education is a human, a certain kind of human being, not a body of knowledge.

I think if we make that distinction, and it’s also a distinction that tracks versus graduate and professional training, then we can say that undergraduate education ought to have at its center a liberal idea that is an undergraduate education should be about the formation of individuals not dominated by disciplinary concerns and not dominated by the project of advancing knowledge. So that’s a useful distinction that I think works in the American system. It obviously doesn’t work in the European university, but it works here. But it’s useful because then when we think about general education, we are thinking primarily as an undergraduate project that there should be a portion of the undergraduate education that is dedicated to this holistic kind of education. And there could be another portion that is more specialized and that prepares students for the job market or for further study.

I think that liberal idea is where that track of liberal education and the undergraduate experience is where citizenship education has a place or character formation has a place. And I do think that there has to be some sort of recognition of commonality and for example, Adrienne, you were saying you want the pluralism, but you want people to do it in a rigorous way. Rigor emerges as a kind of unifying commonality. And there are others that one can imagine a faithfulness, the truth, a respect for diversity of opinions. There are a number of intellectual virtues that I think are not in opposition to pluralism, but pluralism and diversity, the realization of pluralism and diversity is a kind of harmony. Otherwise, you just have chaos. You just have difference. But what makes difference valuable is our capacity to bring those differences to bear on common territory without the commonality, the pluralism, and the difference is just meaningless and it's a cacophony. I think the challenge of general education is to find those points of convergence and those points in which the diversity that we value can harmonize for common forces.

Abram Van Engen: My problem with Fish is that I think there isn’t such a clear distinction between analysis and advocacy. The clearest way to think about that is you’ve got a 14-week semester, you’re going to have to choose some texts to teach on the humanities and many, many, many that you’re not going to teach. So already the choice of what you are going to analyze is a kind of advocacy for those texts. And this just came home to me when he said that civic capacities won’t be acquired simply because you’ve learned about the basic structures of American government or read the Federalist Papers. And then he says both are good things to do, but he doesn't say why they are good things to do. I think one of the reasons they are good things to do is because you might learn civic capacities out of them, or your capacity for civics might be expanded by reading them. So I just think the difference between analysis and advocacy is not so clear cut.

Fish starts his chapter by saying if you read the mission statement of almost any college or university, it will lead you to think that it is the job of an institution of higher learning to cure every ill the world has ever known. And my response is, “Well, kind of isn’t it? Isn’t that the point? Aren’t we producing students to be able to address any ill of the world?”

Roosevelt Montás: I think when you think of education as liberal education, then yes, it is to address every ill of the world, the ones that we can think of, and the ones to come.

David Decosimo: I think that if we make curing the world’s social ills the goal of the university, I start to lose track between the difference between an NGO, a super PAC, a vocational school, and a university. I also start to wonder where we have contemplation and the goodness of knowledge and its enjoyment and community for its own sake. Where is that going? And then isn’t it then also the case that we are kind of signing our own death warrant? Because we’re saying the measure of whether we should exist is whether we are succeeding in curing the world's ills. And it seems to me that there are lots of institutions other than the university that can probably do that a whole lot better. And that doesn't mean that those other things aren't incredibly important and incredibly valuable. I'm just asking the question of whether the university is the appropriate locus for that or whether that aim is the right one for the university.

Suzanne Shanahan: When Abram mentioned that the university ought be responsible for the ills of the world, I suddenly thought I was in a different room. Because in mid-August I had a version of this conversation in Santiago, Chile. The four largest universities there have had leadership changes. And every single new leader said that their effort was to bring together a liberal education combining a strong core of general education with expert education. Because the purpose of higher education in Chile is to save Chile from the extraordinary inequality, racial divisions, and seismic, geological problems. And their formative goal, if they were to say the one thing every student needs to leave with is, a robust sense of themselves as citizens responsible for the future of Chile. And I would love us to be able to think about how we bring liberal education together with geologists who are going to solve this extraordinary problem that Chile has with earthquakes as part of what we’re thinking about today. Because I think that intersection is where there are profound opportunities to cultivate citizens who have a strong sense of purpose beyond themselves, who care about things besides their own income or their own family. And how we might find that space is really exciting.

Adrienne Davis: I think there are lots of ways to engender faculty to care. But it often goes back to needing money because when you tell faculty “I’ll give you a stipend to work on this, and it’s competitive and not everybody gets to do it,” then suddenly you can get faculty interest.

Kavin Rowe: It occurs to me in thinking about the sorts of things that we teach that we haven’t said much about the kind of people that teach them. I immediately start thinking about actual colleagues I know, and some of them I would like to teach young people about having to become a mature being and others of I think, “no, please don’t.” And it’s not just a machine that puts teachers in place. You have to do some actual sorting about the capacities of the teachers. And that gets to the question of how much you want to actually do. I mean, what sort of teacher makes the best teacher of a police officer may be a different thing from who can teach college students. And there’s a sort of range. And then you would want to think about who we actually have that we can count on to teach this sort of thing that we want the people to become.

Chad Wellmon: To go back to David, Abram, and Adrienne, and your conversation based off Abram’s provocation about solving all the world’s ills. DuBois offers a kind of a conceptual distinction as he’s arguing with late 19th and early 20th century progressives who are trying to turn universities into, as he puts it “instruments of social reform.” And he makes this distinction between the mediate and immediate ends of intellectual activity. The mediate aim of the disciplined study that he’s working in, and devotes his life to, is social reform. And he's very straightforward about that. But he said that becomes impossible without the immediate aim of his disciplined study, which he just calls “truth seeking.” And so I think that’s one way to think about the university’s causal relationship to these aims. It’s a conceptual distinction between mediate and immediate aims.

“Educating in this reflective way requires a certain amount of money. And the money is only in certain places.”

— Elisabeth Kincaid

Elisabeth Kincaid: I’m trying to figure out a way to ask the question that’s really weighing on me, which is the question about money. I’ve taught at a Roman Catholic seminary, which worked with time for contemplation and prayer, and that economic model worked because the assumption is everybody here has vowed celibate living and a vow of poverty. You don’t need that much money to make this work and to have that space. And I’ve taught at an Episcopal seminary. To Frank’s point, the Episcopal Seminary is living off the remnants of being the church of the elite. There’s a lot of money in the background. All of our students are going to go and get pensions set up by JP Morgan in the 1910s. So they had the space to do this sort of education.

But when I’ve taught in other schools and specifically Loyola in New Orleans, and my students would say to me: “The reason I’m here is because I don’t want my mother to live in poverty. The reason I’m here is I grew up in the New Orleans school district school system, which is terrible, and this is my only way out.” And there’s no money to give them that space for reflection. Educating in this reflective way requires a certain amount of money. And the money is only in certain places. So I guess back to Frank’s point about the elite: is our job only to educate the elite for citizenship?

John Inazu: One thing that strikes me is that we have in this room an overrepresentation of people who did actually win at the game. Some of you came from modest circumstances. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that the institutional form that we succeed in is the best, most efficient, or even morally defensible way of education, particularly when you think about the unbelievable cost of this way of education versus alternative possibilities of citizenship formation. For example, military basic training was in some ways a lot more formative for me than college. Part of the brilliance and the effectiveness of military formation is you don’t get to opt out of anything—it’s not on your terms. But that is actually essential to forming people. And if you gave me a budget equal to the size of the top hundred elite schools, I could form citizens across the country through something like military basic training. And so I’m left wondering about a totally alternative model. If the goal is something like forming democratic citizens, then that could be done at far lower costs and far more equitably and broadly.

![Picture on the left

Church Under the Bridge. [Facebook Profile]. Facebook. Retrieved November 4, 2025. https://www.facebook.com/p/Church-Under-the-Bridge-100064392743740/

Picture on the right

Dorrell, J. (2016). Church Under the Bridge | Waco Histor](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/690bc761352bf153d4b30071/1dee78bd-bfc8-4f36-acc1-c0a5385e06da/Hendren+Wash+U+slides-3+copy.jpg)